by meghanleborious | Feb 27, 2022 | Notes on Practice

Today I went to the woods to dance for the third day in a row. The only footprints in the surface of the snow were my own from the previous day. I choose a spot close to the river and walked a big circle to dance inside of to set a container for myself.

It took some exertion to get started given the crusted over surface of the snow, but once I moved around more, taking care to visit every part of the circle, the going got easier.

The low afternoon sun cut through the bare trees and dazzled my vision. It was hard to avoid meeting the sun’s eyes, and brightly colored yellow, then red afterimages flashed on the snow, always disappearing as soon as I turned to them.

In Flowing, my focus tends to be soft. My eyes are slightly lowered, gaze often resting not far from my circling feet. When I’m dancing with others, I sense and internally acknowledge the people around me, but don’t typically make direct eye contact.

In the woods today, it took awhile to let some of to-do list types of thoughts run though. As I brought my attention again and again to my feet, my breath started to deepen, and my senses became more noticeable.

The first sign that Staccato started to break through was that my gaze lit on a tree across the clearing, and I directed my attention to it. In Staccato, my eyes lift to my personal horizon line. They seek and find. I turned sharply to a different tree, then to a spot in the river. Then to yet another tree 180 degrees behind me, aligning my gaze with sharp, clear gestures.

Dancing with others, this is often the moment that I’m called to partnership. When I’m drawn into someone else’s field and I don’t question it, I just move toward and step in. I might meet someone’s eyes and smile. I might do a full turn while tipping my head back to hold their gaze the entire time. I might have a conversation in gestures, or any other kind of exchange.

Today I was strongly aware of the transition from Staccato into Chaos, because of how my relationship to gaze shifted. In Staccato, my eyes would find something, then I would lock into it, narrow my field, and respond. But when my gaze started to land on things at the same time that I was starting to respond to them, I started to feel the shift into Chaos. Whereas in Staccato, my vision was targeted, in Chaos, vision started to attend more to the peripheries, scanning rapidly for movement at the edges of my field of vision. As my head and body released more and more, vision started to get blurry, and flashed through sky, trees, river, feet, and snow with increasing speed.

Today I was strongly aware of the transition from Staccato into Chaos, because of how my relationship to gaze shifted. In Staccato, my eyes would find something, then I would lock into it, narrow my field, and respond. But when my gaze started to land on things at the same time that I was starting to respond to them, I started to feel the shift into Chaos. Whereas in Staccato, my vision was targeted, in Chaos, vision started to attend more to the peripheries, scanning rapidly for movement at the edges of my field of vision. As my head and body released more and more, vision started to get blurry, and flashed through sky, trees, river, feet, and snow with increasing speed.

In Lyrical something interesting often happens when I’m dancing outside. I start to notice sound in a different way. It’s like all the racket I was making in Chaos ceases and hearing is turned up. Sometimes my gestures are similar to how I was moving in Chaos, but it sounds really different. My gaze lifts up and sees more space. I start to see patterns everywhere – the ripples on the water, the overlapping branches and roots, the drifted snow.

When I’m dancing with others, I might meet different people’s gazes and move quickly throughout the room, taking everyone as a partner, seemingly at once. I might also dance with something I’m sensing just above the people, or race through with a partner, playing hide-and-seek or lead-and-follow, as connected when we’re side by side as we are across the room, somehow seeing each other even when our line of vision is blocked by other dancers.

In Stillness, the gaze might become internal and (for lack of a better word) cosmic. This is when mundane vision might recede. Sometimes it’s like I turn inside, and the quality of that inner looking opens up a new doorway. Then I might start to see past the surfaces of things and experience a different level of reality – the relative yielding to the absolute, which is always available to us, yet is often invisible.

Today was no exception. One wide plane of undisturbed snow glittered green, purple, pink, and blue. I tried to capture it as a photo but none of the magic came through and my engagement shifted once I took on the camera’s gaze, the viewer’s gaze, the reader’s gaze.

I sank down onto my knees and bowed, grateful for all I’d seen.

Meghan LeBorious is a writer, teacher, and meditation facilitator who has been dancing the 5Rhythms since 2008 and recently became a 5Rhythms teacher. She was inspired to begin chronicling her experiences following her very first class; and she sees the writing process as an extension of practice—yet another way to be moved and transformed. This blog is not produced or sanctioned by the 5Rhythms organization. Photos and videos courtesy of the writer.

Meghan LeBorious is a writer, teacher, and meditation facilitator who has been dancing the 5Rhythms since 2008 and recently became a 5Rhythms teacher. She was inspired to begin chronicling her experiences following her very first class; and she sees the writing process as an extension of practice—yet another way to be moved and transformed. This blog is not produced or sanctioned by the 5Rhythms organization. Photos and videos courtesy of the writer.

by meghanleborious | May 19, 2020 | Notes on Practice

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about feet.

The late afternoon sun on my closed eyelids lets me see the orange-red blood in the eyelid’s tiny capillaries. Turning away from the sun brings them back to shadow. My eyes still closed, I turn into the dazzling sun and back into shadow again and again, moving with my own breath. Bird song filters down from the tallest tree in the yard. Wind starts as a rustle at the tops of trees, then causes a progressive cooling on the exposed skin of my arms and face, as my feet softly turn, feeling every curve and dip of the ground.

But I begin with the end, with the rhythm of Stillness. There were so many things that led me here, to this quiet reckoning, to this cloudless sky.

***

The day was already getting away from me; and I was tempted to cancel or rush through a video call I had planned with a friend. And then it seemed that every corner of the house was full of sound: the vacuum cleaner, my ten-year-old son, Simon, on his own video call, lawn-mowing outside. I keep moving around trying to find a place I could actually hear and settle down. I’m sure I seemed spastic, and my friend even suggested it might be better to postpone. Finally, I found a quiet corner and settled in.

Speaking with her reconnected me to myself, and I left the call thinking it was time well spent.

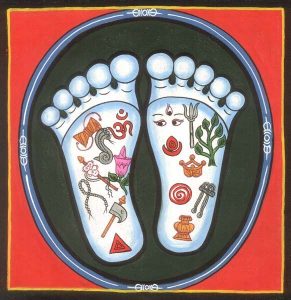

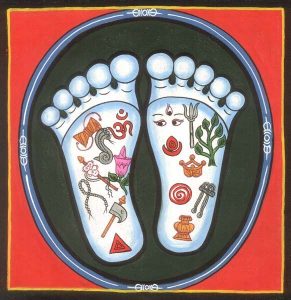

Over the past few days, I’ve been engaged in an ongoing discussion with another friend on the subject of feet. She is deeply immersed in the practice and teaching of yoga, and is also a dharma teacher. She wrote about how the soles of the feet are connected to the different regions of the body, and how the feet are really the beginning of the chakra system. She also shared that there are many images depicting the feet with fanned flower petals underneath them, indicating that the entire body is supported by the “lotus feet.” She wrote, “As the lotus feet ‘bloom’ they encourage similar openings in the nervous system and subtle body.”

immersed in the practice and teaching of yoga, and is also a dharma teacher. She wrote about how the soles of the feet are connected to the different regions of the body, and how the feet are really the beginning of the chakra system. She also shared that there are many images depicting the feet with fanned flower petals underneath them, indicating that the entire body is supported by the “lotus feet.” She wrote, “As the lotus feet ‘bloom’ they encourage similar openings in the nervous system and subtle body.”

I found that I had some things to share from the perspective of the 5Rhythms about the subject of feet.

It is the feet that connect us to our intuition, our instinct. One of my teachers, Kierra Foster-Ba, often says, “We, like any other animal, get a lot of information from our feet,” including vibrations in the ground. In this way, the feet can be seen as a gateway to primal, unconditioned awareness.

Each of the 5Rhythms is associated with a body part; and the rhythm of the feet is Flowing. It is considered the receptive rhythm, where we are letting in, sourcing, and gathering energy and information.

I’ve been investigating my relationship to Flowing anew of late, especially as I’ve been dancing in the woods, gardening, and attending to nature’s cycles like the moon and the seasons since retreating from NYC because of the pandemic.

In 5Rhythms, some talk about “finding the feet” as the measure of embodiment in 5R practice. It is as though to what degree you have “found your feet” indicates your level of attainment. This can be interpreted in a straightforward way–actually paying continuous attention, on purpose, to the physical feeling of the feet on the ground.

Personally, I tend to generalize this a little more, and interpret “finding the feet” as establishing and maintaining profound mindfulness, while using the feet as the primary object of meditation.

The entire dance is built from the ground up, and there are times we return to Flowing, even when we have shifted into the other rhythms that follow in the wave: Staccato, Chaos, Lyrical, and Stillness.

***

My first movements into the rhythm of Flowing today seemed twittery, but before long, I resolved to drop my full attention and weight into one foot and then the other, and this opened me into generous, weighted circling. Sometimes my steps were even subsumed and pulled into the larger falling circling of the body.

A different friend shared that in one class she had started to feel bored in Flowing. I could totally relate. For many years, I was so eager to get from the first rhythm of Flowing to the second rhythm of Staccato that I had to force myself to stay in Flowing for longer than felt intuitive. I often felt bored in Flowing. It’s humble edgelessness held little appeal for me, and I was eager for the expression of Staccato and the explosive catharsis of Chaos.

I realized that I had severed my relationship to earthiness, and, in the process, to the ground. It took many years of devoted practice, especially working with the rhythm of Flowing, to begin to reclaim this relationship.

Thanks to my own song choices, I was dropped abruptly from Flowing into the rhythm of Staccato. I occasionally let out a warrior cry, and my body was dynamic, alive, finding every diagonal, bending and flexing, bouncing up and curving down, sticking my butt way out, then pushing my pelvis forward, with my knees and elbows talking loudly.

Thanks to my own song choices, I was dropped abruptly from Flowing into the rhythm of Staccato. I occasionally let out a warrior cry, and my body was dynamic, alive, finding every diagonal, bending and flexing, bouncing up and curving down, sticking my butt way out, then pushing my pelvis forward, with my knees and elbows talking loudly.

Though I so needed Chaos today, I had to talk myself into it. I imagined my body was moving on a roller coaster track, and my head was like the last car that hops a bit off the track at the end of the train’s whipping gesture. I had a lot of energy in this part, though it wasn’t until the second chaos song that I actually moved intensely enough to be out of breath. At one point the music paused and I leaned forward and held my hands out behind me then crashed them together, rocketing back as the beat kicked back in. I used up all the space available to me, kicking my heels behind me, cross-back-stepping, and flinging my arms up.

Lately in Lyrical, the top of my chest rises up. Today, I was so happy. I’m so happy for myself, that I got to be this happy. I found a tiny little mound of earth to stand on top of, twitter down the side of, twitter down the other side of, back, front; and then the beat dropped again, and every bit of me coiled and bounced, it was like I was on a trampoline, my arms flying way up, body effortless.

Lately, I sometimes make videos of myself dancing alone, and today, as I watch the video, I cry. I can’t believe how lucky I am, that I get to experience such joy. Lyrical only opened itself to me after many dedicated years of working with the ground, with the feet, and with the rhythm of Flowing. Before then, it felt totally unavailable.

I suspend my leg forward and pause, bounce back, then suspend it backward and pause.

Then, this beautiful song comes through the speakers and I close my eyes, noting the variations of light on my inner eyelids. And that brings me back to the beginning, to the Stillness I opened with, to the flashes of light and birdsong, to the rustling breeze and its effect on my skin.

The last thing I do before breaking down my equipment and going inside to cook dinner is walk on the soft earth, my feet alive and knowing, absorbing the messages the earth needs me to hear.

May 18, Broad Brook, Connecticut

Images: Simon’s feet on grass (photo by Meghan LeBorious), The Auspicious Lotus Feet of Lord Vishnu (vivianlawry.com), Self attending to music (photo by Meghan LeBorious)

This blog consists of my own subjective experiences on the 5Rhythms® dancing path, and is not sanctioned by any 5Rhythms® organization or teacher.

by meghanleborious | May 1, 2020 | Notes on Practice

A lone duck appeared while I was meditating on the bank of the modest Scantic River. The duck was industriously chugging her little head back and forth like a small child on a big wheel, letting out a periodic call of “quack” as she floated by. I was touched by her efforts, smiling and internally cheering her on.

A lone duck appeared while I was meditating on the bank of the modest Scantic River. The duck was industriously chugging her little head back and forth like a small child on a big wheel, letting out a periodic call of “quack” as she floated by. I was touched by her efforts, smiling and internally cheering her on.

It’s been over five weeks since I left NYC along with my ten-year-old son, Simon, to join my parents in Northern Connecticut and try to wait out the pandemic.

In the beginning I practiced ferociously. Every day, every spare minute. Zoom 5Rhythms classes, individual waves, dancing on the grass in the backyard, dancing in the woods, dancing in the little practice space in my temporary home.

Every session started to blend together. My knee started to hurt. I started feeling generally left out and isolated. Simon started to act up, no doubt suffering from the loss of contact with people his age, and the pervasive sadness and uncertainty.

Yesterday, I decided to lighten up for a few days, and give myself a little distance from practice.

I juggled my afternoon options: should I go for a run? Meditate? Do yoga? Dance a wave? What did I most feel like doing?

Since the day was lovely and several not-lovely days were forecast, I settled on a run in the woods. I felt safe going hard on the soft trail, and lost myself in moving. I paused to take photos along the way, loving the visual narrative the images were revealing.

I came to my favorite spot, the convergence of a small river and a large stream, with a grassy point between the two. There, I decided to dance a wave. Easing into the rhythm of Flowing, I moved up and down a small hill, dipping and casting into low circles.

At a workshop once, in Flowing, the teacher advised us to work with gravity as though we were dancing on a hill. Being on a hill, I played with rising and falling, and the shifts of gravity as I moved up and down it in hoops and arcs, to a soundtrack of babbling water splashing over a fallen tree.

Someone appeared in the woods on the opposite bank, and I tried not to meet his eye. Staccato crept up, then drifted back into Flowing. I moved back into Staccato, with punctuated exhalations, low-sunk gestures, and emphatic movement declarations.

It took me a while to warm up to Chaos, but it eventually presented itself. I jumped and leapt, releasing my head and encouraging myself to go all out, despite the person across the river who might be watching, and who I was pointedly avoiding.

I practically skipped the rhythm of Lyrical, as suddenly the hum of the woods brought me straight to Stillness. I consciously called on Lyrical, though, and found several minutes of light, creative movement. It wasn’t until then that I noticed the person across the river had gone. It was possible I’d been alone for most of the time, so apparently I’d wasted my energy in purposefully ignoring him and psyching myself up to go all out even if he thought I was weird.

This place calls me to Stillness, and I was content as I finally settled into it. In Lyrical, I danced with everything that was moving. The small animals, the wind in the trees, the passing cars, the complex currents in the river. I even started to move with sound waves like bird calls, the rush of trees, and the sounds of the water.

I remembered an experience at an underground dance party many years ago. Thousands of partyers were crowded into an old warehouse, and giant bass speakers shook the architecture. At this party, they also had complex light projections that twisted and morphed. I spent the entire night in rapture, dancing to the light show. As an artist, realizing that I could dance to visual cues, not just music, blew my mind.

Since then, I’ve learned that I can dance to anything, to everything. A passing train. A sequence of feelings. An announcement over a loudspeaker. The receding tide. One of my neighbors in Williamsburg, Brooklyn kept pigeons, and I used to dance with the swirling, diving flock as they raced around in response to his direction. Today, moving to everything in the woods reminded me of that first opening.

Curiously, though I was in the woods alone, it started to feel hectic. I decided to let go of the hectic feeling, but to continue to move with everything around me, including wind; and the curves, intersections, and complexities of currents. Nothing changed but suddenly I was enveloped by silence.

Later, I spent time doing yoga, but I wasn’t trying to get a workout in, wasn’t trying to be as present as possible, wasn’t doing anything except following my inclinations and feeling the joy of having a body.

Today, after a full day of online work, I decided to join an afternoon 5Rhythms Zoom class.

Today, after a full day of online work, I decided to join an afternoon 5Rhythms Zoom class.

I had to get Simon settled into an activity, so I joined the class a little bit late, then fell happily into the rhythm of Flowing. I’ve really been into grounding lately, much more than usual, and I exhaled as noisy energy poured down my legs into the ground. Today, I picked up a weighted meditation cushion, and started using it much like I used the hill yesterday, to experiment with gravity and momentum, at times dropping it around me in circles, passing it hand to hand. When I wasn’t holding the cushion, I let my arms be soft and fall around me as I moved in endless circles.

I discovered that the meditation cushion had a sewn-on handle as the music transitioned into the rhythm of Staccato, and I continued to play with weight and momentum, now pausing with the cushion on my side, on my back, at times letting it pull me through emphatic movements, my elbows sharp. I also experimented with holding the cushion in front of me, dropping it, then using its momentum to rush me straight across the small circle I was dancing inside of.

This, too, reminded me of my experiences in the underground dance world of the 1990’s. I was a fast and athletic dancer, and would imagine I had weight in my hands and feet to source power from the ground: to land, coil, and fling myself into all sorts of dramatic gestures. Once a group of people told me they had come from a neighboring state to see me dance this style at a local club’s jungle music night. It was a cool compliment, but by then I was trying to detox and withdrawing from club dancing. Shortly after, I withdrew from dance altogether for several years.

In the practice video I made for my own curiosity, I seemed very committed in this part, though I remember that thoughts of work were occasionally distracting me. I paused to give an instruction to Simon. Watching it I acknowledge the reality that it’s rare for me to be able to take a full break from parenting to practice, especially since we’ve been staying at home and I am now his parent, teacher, and playmate all-in-one.

I thought I was flat in Chaos, but watching is fascinating today. My head rolls me around on my shoulders, hips released after a long yoga stretch session before dancing, sending movement through the spine and into this lolling head. I pause again to say something to Simon, then drop my head again, and bounce back and forth, then fall into side twisting and spinning.

At the outset, Lyrical was elusive again today. But I started spinning my hips around, almost like rolling a hula hoop and followed it into motion around one leg and then the other, and soon into pauses and full extensions.

My hands look like two beautiful racing creatures in Stillness, then I shift into simply stretching. I paused again to say something to Simon, then in one final shape before clicking “leave meeting.”

I was hoping some revelation would come through before finalizing this text, but sometimes it isn’t so obvious. Sometimes the revelations aren’t epic or picturesque, but come in tiny increments, in daily practice, in patient engagement.

Good thing I took a break from practice. It helped me to feel more responsive and curious, though truthfully, I don’t think I actually “practiced” any less.

April 29, 2020

by meghanleborious | Aug 24, 2018 | Other Writings

Wild and Precious: Breastfeeding As Formal Meditation Practice

Resting against the wall, breastfeeding my tiny son in the quietest stretch of night, I watch from the fourth floor as the silver line of the J-train glides along its raised track and over the East River. A blizzard that encased New York in silence hit a few days ago, leaving city buses stranded in the snow on Manhattan’s busy avenues. Square shovelpaths above the height of my waist have been cut into the deep snow so the sidewalks look like magical labyrinths. The scrape of a shovel on pavement resounds from far away. Inside the room, candles flicker on a low table. The baby, Simon, who is supported by the curve of my arm, has his eyes closed and is sucking patiently, perhaps asleep.

About halfway through pregnancy my mother asked if I planned to breastfeed. “Yeah, I guess,” I shrugged, “If I can, I will, if not, I’m not going to worry about it.” Coping with volatility at home, the question of whether or not to breastfeed seemed like the least of my problems. I hadn’t thought much about how I would give birth either, for the same reason.

Despite little preparation until two weeks before, labor went quickly and smoothly. My as-yet-unnamed son rested easily in the palm of his father’s hand, blinking his dark eyes slowly, like a miniature tortoise. The midwife passed him to me, telling me to try to feed him. I contorted my shoulders and twisted my spine into an awkward shape, holding the baby stiffly. She put her hands on her thick hips and shook her head. “No, not like that. You have to relax. Like this.” She adjusted me, but I still felt uncomfortable and ill at ease.

We left the birthing center just eight hours after Simon was born. At home, we took turns holding him tenderly. I did my best to feed him, but struggled to get him to latch properly, and worried that he wasn’t getting enough to eat. In the first few days, he lost weight. As I understand, newborns have “extra fluid” that they lose right away, and it takes a week or two to regain their birth weight. Still, I felt concerned. In a way, it’s like mothers are set up to worry right from the beginning.

My friend Dina, an RN, came to visit. She taught me “the football hold,” placing the baby with his belly on my forearm, and re-structuring the armature of pillows around me to better support Simon’s six-pound body. Soon after, he started to gain weight.

At night, I tucked pillows around myself so I wouldn’t risk rolling over, and placed Simon on my chest. We slept like that, chest to chest, for six months or more, his tiny body rising and falling with my breath, his arm draped down the side of me, his fist too small to even reach the mattress below.

For our first months together, days and nights became indistinguishable as time lost its workday edges, flowing along in response to Simon’s needs. Many times, the sky lit with sunset before I felt I’d officially settled into the day, and before long, another sunrise would light the room, and another purple sunset.

Less than two months before Simon was born, I lost my job as a freelance textile designer. Fortunately though, I qualified for unemployment and managed to stay with Simon nearly full time for the first two years of his life.

At first, Simon seemed to eat all the time, sometimes for hours at once. In the beginning, I might talk on the phone, craft a task list, or even watch an occasional movie while Simon breastfed. As the weeks progressed, and the gestures of breastfeeding felt more and more natural, I started to really love it. I loved watching and holding Simon, his tiny hands, his curious eyes, his dark, expressive eyebrows, his patient breath.

I learned an important lesson from Simon’s father, Eulas. From the start, I was determined to seem competent and together as a mother, believing that I needed to make it look easy. On a course to fuss from day one, I attended over-carefully to the mundane details of Simon’s experience. Once when he was just a few days old, I watched Eulas hold him, supporting his body and gazing into his eyes, completely still. He was fully present for our tiny son, who was still adjusting to breathing air and to loud sounds and wind and clothing. “Wow. I want that,” I thought. The hell with spending my energy worrying about red tape, and in the process missing opportunities to connect with the miracle of this brand new human being. I decided then to re-set the maternal pattern of worrying and fussing that had quickly emerged, that had seemed almost inevitable, and to emphasize being fully present instead.

I recalled a teaching I’d encountered at Insight Meditation Society, where I’d done a silent retreat a few years previous. It was just a short passage set in a modest biography about Dipa Ma, a saint within the Vipassana tradition. Dipa Ma was a householder who did not seek meditation training until her mid-forties, then managed to attain full enlightenment in a remarkably short time. After her realization, she guided many along the path to enlightenment. One of her first students was a woman named Malati Barua, a widow who was raising six children on her own. According to the biographer,

“Dipa Ma, believing that enlightenment was possible in any environment, devised practices that her new student could carry out at home. In one such practice, she taught Malati to steadfastly notice the sucking sensation of the infant at her breast, with complete presence of mind, for the duration of each nursing period” (Schmidt, 38-39).

Going back to this text, I decided to read it as practice instructions, and apply it to my own experience. From then on, whenever Simon was breastfeeding, I considered it practice time. I did not watch TV, text, read, shop online, or talk on the phone. Instead, I brought my attention to the rhythmic sensation of Simon sucking at my breast. When my mind wandered, I brought it back again to this sensation, taking it as the primary object of meditation.

Using breastfeeding as a formal meditation practice might be seen as the opposite of “brexting.” A recent study published in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior showed that there were distractions in half of infant feedings, and that about 60% of those distractions were due to smart phones and other technology–possibly linked to problems with eating habits later in life.

The patch of woods ringing my parents’ yard is layered densities of green, dark leaves and their pale undersides. Simon, four months old and having just breastfed at length, is sleeping on my lap; and I continue to practice, now bringing my attention to the feeling of holding him, my own breath, and the dynamic forces around me: wind, moving clouds, rustling trees, bird activity, crawling insects. A hummingbird hovers just a few feet away, interested in some colorful partylights on the deck that it seems to think might be flowers.

Mindfulness meditation is often focused on the breath, but a practitioner can choose any object to focus on. In the beginning, the instruction is to notice if your attention wanders and gently bring it back to the thing you decided to focus on–in this case the physical sensation of breastfeeding. The more we come back to our focus, the more we build up our capacity to be mindful. Being more mindful allows us to be less anxious, more focused, more loving, and fundamentally happier, even as life continues to present its ups and downs.

Before giving birth, I feared that it might be hard to continue my well-established meditation practice once the baby came. Instead, because of using breastfeeding as a formal meditation practice, I felt like I was on retreat for the first months of Simon’s life. Blissful sensations arose frequently despite the painful challenges that I continued to face in my relationship with Eulas, which ended after eight tumultuous years around my first Mother’s Day.

In late Fall, when Simon is ten months old, we visit my cousin and her wife in Vermont. They’ve renovated an old farmhouse; and it sits on a wooded, sloping acre, complete with an apple orchard. They head for work, leaving us to explore on our own. After walking patiently around the property with attention to all of our senses, we settle onto a big, woven-rope hammock so Simon can breastfeed and slide off into a nap. I hang my foot over the side of the hammock, rustling some dry leaves and rocking us by pushing against the ground. Simon snuggles close to my body, falling into a trance of contentment. I practice, holding him and continuing to rock back and forth in the hammock, intentionally noticing the physical sensations of breastfeeding. The trees are majestic, soaring high overhead. Clouds rush behind them. A horizontal leaf drifts all the way down from the high branches, zigzagging patiently to the ground.

That I was not working for the first two years of Simon’s life made it easier to use breastfeeding as a formal meditation practice, but Dipa Ma specially designed this practice for mothers who are pressed for time, and I believe it is a viable option for maintaining (or even deepening) a meditation practice during the first stretch of motherhood.

We think we are so busy, but the truth is that sometimes we make ourselves busier than we need to be because it makes us feel important. The more we tell ourselves we are busy, the more we amp ourselves up and lose touch with what is actually important. Conversely, the more present we are, the better we are able to be strategic about mundane necessities, to express love, and to delight in the tiny, patient experience of welcoming a new human to the world.

In the words of the poet Mary Oliver,

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do

With your one wild and precious life?”

This essay is dedicated to Lauren LeBlanc, in gratitude for her encouragement, literary skill and insight, and also for her dedication to excellence in mothering. It is also dedicated to my own mother, Betsy LeBorious, one of my two first and best teachers.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4662912/

https://www.scpr.org/news/2015/09/24/54595/brexting-impacts-baby-bonding-during-breastfeeding/

https://www.elsevier.com/about/press-releases/research-and-journals/mothers-often-distracted-during-breast-and-bottle-feeding

https://www.amazon.com/Dipa-Ma-Legacy-Buddhist-Master/dp/0974240559

(First published Muthamagazine.com, July 19, 2018)

by meghanleborious | Jul 9, 2016 | Notes on Practice

While everyone in New York is suffering through a heat wave, I have been wearing sweaters and still shivering. This is my seventh day in chilly Ireland, traveling with my six-year-old son, Simon. First, we explored the astonishingly beautiful western region of Connemara. In Connemara, there is water everywhere. Lush vegetation goes all the way to the edges of every puddle, lake and river, giving the impression that everything is extremely full. Rock juts up through the green in impressive, unpeopled, ancient mountains. Rolling fields patchworked in different greens and hemmed by squared stone walls stretch all the way to the ocean’s edge. Textured layerings of green plants cover everything, even overtaking rock walls and sea cliffs—though in an entirely cheerful proliferation, nothing of sinister engulfment or of overwhelming insistence.

On our first full day in Annestown, on the Southeast coast of Ireland where we are staying at the house of a good friend, Simon got completely soaked. I didn’t even bring a change of clothes to the beach because it didn’t cross my mind that he might frolic in the waves on such a foggy, cold day; but he met a new friend and they raced happily in and out of the water. (It should be so easy for all of us! “You are about my size. You are willing to run with me. You are my friend!”) Truthfully, it seems almost that easy here with adults, too.

The next day, Simon and I trekked from late morning until evening in search of a local castle. With some trial and error, we managed to locate a nearby path our friend had mentioned that leads to the ruined palace. As we neared the castle, the path grew narrow and steep, with vegetation enclosing us as we ascended. Having been stung by nettles the day before, Simon moved forward hesitantly. Emerging, we were the only castle visitors. There was a discreet board with information in Irish, but no other signs of tourism. The castle rose above us, overgrown and chipped away, but nonetheless impressive. I put the picnic bag down on a flat, grassy spot, thinking we would explore the interior, then picnic there. Ascending further, I realized there was yet another, higher, even more beautiful grassy spot to picnic that looked for miles over green farmland. We explored the one room that was left of the castle’s interior, looking out through the window opening on each of four sides, then sat down to a picnic of Irish brown bread, sliced turkey and plums.

After our picnic lunch, we spotted a way to climb up a ledge of stones to the castle’s second floor. Perhaps against my better judgement, Simon and I climbed up and took in the views from this even higher perch. I held my breath and kept him away from the edges, still noting that even the roof sported lush turf and abundant greenery. Descending was more challenging; and there was a moment that I gasped with fear, but Simon followed my directions carefully and we made it without injury back to the level of our picnic.

We continued to walk along the path all the way into the next village, and slowly became cognizant of the tiny faery doors that dotted the woods. One was a four-inch tall wooden door carved with celtic scrollwork. Another featured tiny stairs. And yet another—moldings and trim. Most were at a convenient level for faeries and attached to a lower tree trunk. We made offerings of flowers at each door and asked the faeries to help with many special intentions. To my swelling pride, Simon included prayers for the happiness and well-being of the faeries, in addition to many prayers for him, for me, and for friends and family members.

Simon slowed down considerably as he grew tired. At one point, he stopped moving forward and closed his eyes. He began to move his hands slowly, perhaps imitating people he has seen doing tai chi in the parks of New York City. He wanted me to follow him, but soon realized that for this kind of dancing, it was more fun to do it on your own. I, too, moved slowly, my arms gently guiding my my gestures, my breath audible. Wind rustling through the marsh grasses passed through my body. For the first time, I noted that the direction of my gesture might not be the same direction as the energy that moved around me, but the different fields could be in harmony, like the different forces at play in a tide. My shoulders and upper back wanted to unfold and unfurl. (Stillness reveals itself to me in stages.)

Eventually, Simon started moving forward again, and we went to try to find a shop in the village near the end of the path where we heard we could get some ice cream.

Although there are 5Rhythms teachers and practitioners in Ireland, there are no scheduled events during the time of my stay. I am planning to undertake formal, individual practice as soon as Simon starts camp on Monday, though I am not tricked by the pretense that the practice happens only when I declare that it is happening. Instead, I hope I will be open to all the magic that presents—especially when it is as obvious as faery doors.

July 8, 2016, Annestown, Co. Waterford, Ireland

(Note: After this writing I learned about two new instances of police killings of black men in the US, and of the rising tide of rage and mixed feelings in response. I hope this lyrical foray does not offend anyone who is deep in the throes of agony, praying for a new dawn of tolerance and of enlightened policy.)

This blog consists of my own subjective experiences on the 5Rhythms® dancing path, and is not sanctioned by any 5Rhythms® organization or teacher.

Today I was strongly aware of the transition from Staccato into Chaos, because of how my relationship to gaze shifted. In Staccato, my eyes would find something, then I would lock into it, narrow my field, and respond. But when my gaze started to land on things at the same time that I was starting to respond to them, I started to feel the shift into Chaos. Whereas in Staccato, my vision was targeted, in Chaos, vision started to attend more to the peripheries, scanning rapidly for movement at the edges of my field of vision. As my head and body released more and more, vision started to get blurry, and flashed through sky, trees, river, feet, and snow with increasing speed.

Today I was strongly aware of the transition from Staccato into Chaos, because of how my relationship to gaze shifted. In Staccato, my eyes would find something, then I would lock into it, narrow my field, and respond. But when my gaze started to land on things at the same time that I was starting to respond to them, I started to feel the shift into Chaos. Whereas in Staccato, my vision was targeted, in Chaos, vision started to attend more to the peripheries, scanning rapidly for movement at the edges of my field of vision. As my head and body released more and more, vision started to get blurry, and flashed through sky, trees, river, feet, and snow with increasing speed. Meghan LeBorious is a writer, teacher, and meditation facilitator who has been dancing the 5Rhythms since 2008 and recently became a 5Rhythms teacher. She was inspired to begin chronicling her experiences following her very first class; and she sees the writing process as an extension of practice—yet another way to be moved and transformed. This blog is not produced or sanctioned by the 5Rhythms organization. Photos and videos courtesy of the writer.

Meghan LeBorious is a writer, teacher, and meditation facilitator who has been dancing the 5Rhythms since 2008 and recently became a 5Rhythms teacher. She was inspired to begin chronicling her experiences following her very first class; and she sees the writing process as an extension of practice—yet another way to be moved and transformed. This blog is not produced or sanctioned by the 5Rhythms organization. Photos and videos courtesy of the writer.

immersed in the practice and teaching of yoga, and is also a dharma teacher. She wrote about how the soles of the feet are connected to the different regions of the body, and how the feet are really the beginning of the chakra system. She also shared that there are many images depicting the feet with fanned flower petals underneath them, indicating that the entire body is supported by the “lotus feet.” She wrote, “As

immersed in the practice and teaching of yoga, and is also a dharma teacher. She wrote about how the soles of the feet are connected to the different regions of the body, and how the feet are really the beginning of the chakra system. She also shared that there are many images depicting the feet with fanned flower petals underneath them, indicating that the entire body is supported by the “lotus feet.” She wrote, “As  Thanks to my own song choices, I was dropped abruptly from Flowing into the rhythm of Staccato. I occasionally let out a warrior cry, and my body was dynamic, alive, finding every diagonal, bending and flexing, bouncing up and curving down, sticking my butt way out, then pushing my pelvis forward, with my knees and elbows talking loudly.

Thanks to my own song choices, I was dropped abruptly from Flowing into the rhythm of Staccato. I occasionally let out a warrior cry, and my body was dynamic, alive, finding every diagonal, bending and flexing, bouncing up and curving down, sticking my butt way out, then pushing my pelvis forward, with my knees and elbows talking loudly. A lone duck appeared while I was meditating on the bank of the modest Scantic River. The duck was industriously chugging her little head back and forth like a small child on a big wheel, letting out a periodic call of “quack” as she floated by. I was touched by her efforts, smiling and internally cheering her on.

A lone duck appeared while I was meditating on the bank of the modest Scantic River. The duck was industriously chugging her little head back and forth like a small child on a big wheel, letting out a periodic call of “quack” as she floated by. I was touched by her efforts, smiling and internally cheering her on.